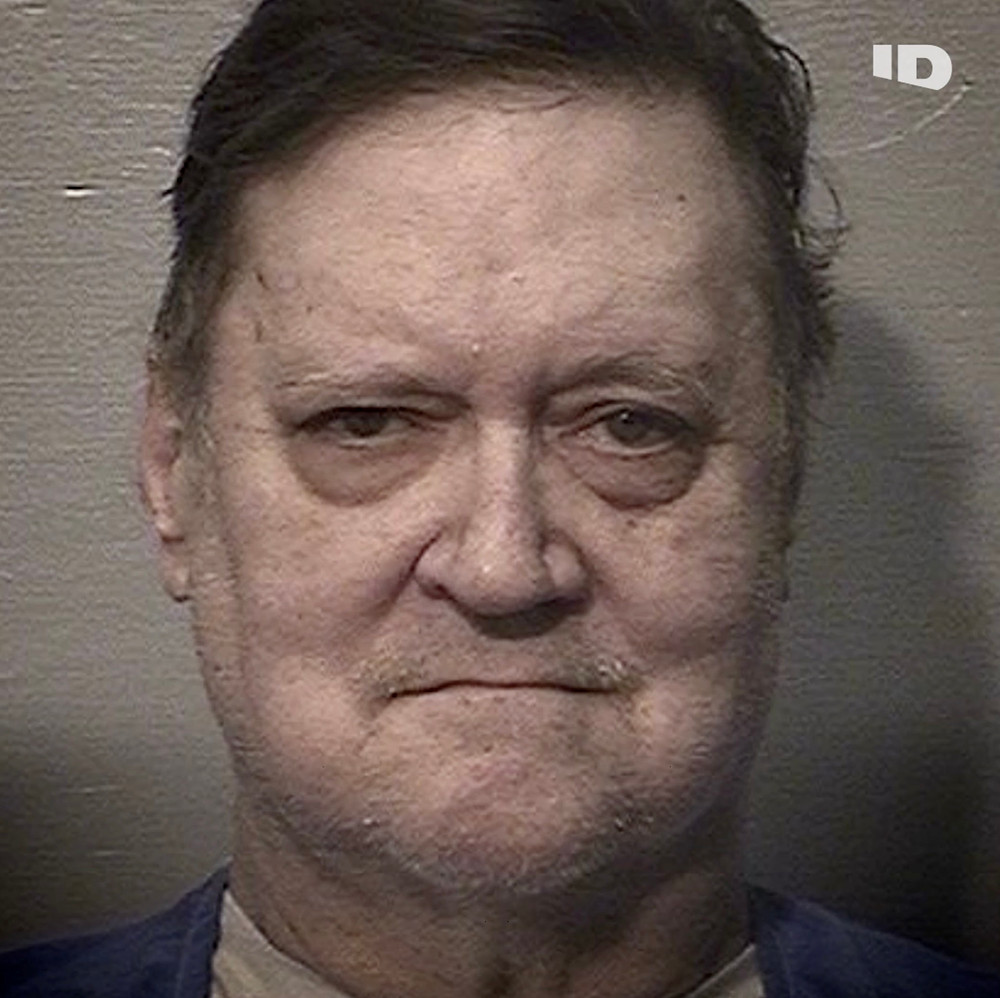

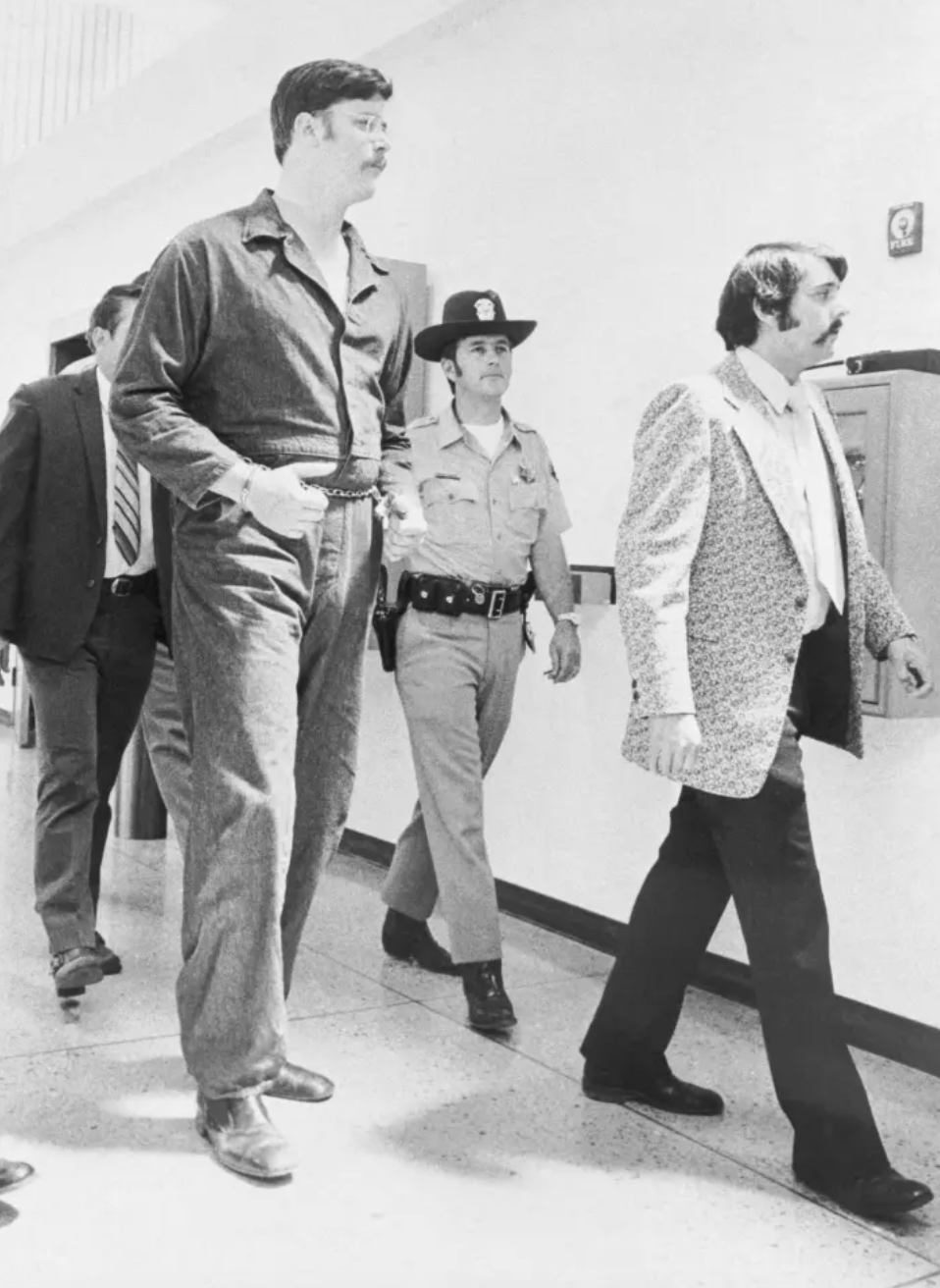

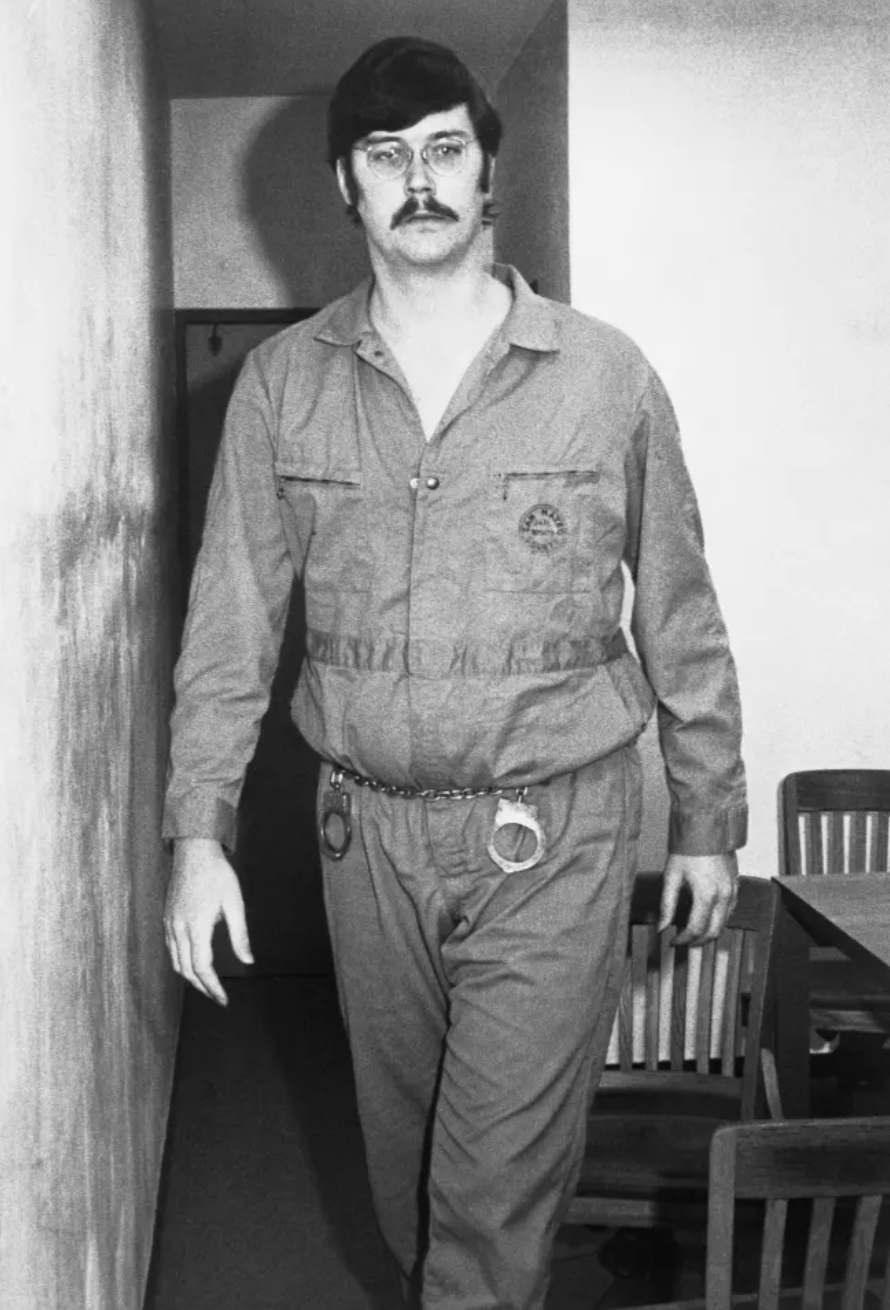

With his perplexing combination of calm intelligence and brutal aggression wrapped up in a 6-foot 9-inch frame, Ed Kemper is a literal and metaphorical giant in serial killer lore. He murdered six college students, his grandparents, his mother, and her friend before turning himself in to the police in 1973. His detailed and uncensored interviews with FBI agents on how his mind works helped form the basis of modern criminal psychological profiling.

We’re examining his personality type using the Enneagram, highlighting and analyzing the cues we think are most important in identifying his type. We relied on the following materials: Ed Kemper: Conversations with a Killer: The Shocking True Story of the Co-Ed Butcher by Dary Matera, Edmund Kemper: The Life of the Co-Ed Killer by Hourly History, and Mindhunter: Inside the FBI’s Elite Serial Crime Unit by John E. Douglas and Mark Olshaker (which was also the bases of the Netflix show “Mindhunter ” that heavily featured the Ed Kemper character ). The Enneagram type we’ve assigned to Kemper is our best guess, given our observation of his motivations, decisions, behaviors, speech, body language, and more. We’ll explain which type we think he is and why, using examples when relevant.

Note that type descriptions below come from Blueprint, our Enneagram app . And be warned: the following post gets graphic, but we think it’s necessary to include some of the gory details because they help illustrate what kind of person Kemper is.

Base type: Five (the Investigator)

Our best guess for Kemper is a Five. Fives want to avoid feeling incapable and incompetent. They focus on accumulating knowledge, building mental models, mastering areas of expertise, exploring reality, searching for the truth, and reducing their dependencies on others. They want to preserve internal resources to build competence, so they isolate themselves from others and retreat into their minds. At their best, they are open-minded, objective, and visionary, perceiving the world as it truly is and making innovative discoveries.

Subtype: Five with a Four wing (the Iconoclast)

Our best guess for Kemper is a Five with a Four wing. The Iconoclast is inventive, cerebral, intellectually-intuitive, unassuming, abstract, eccentric, disconnected, subversive, and reclusive. They are contemplative and astute explorers, but can be antagonistic and nihilistic.

Event timeline: Ed Kemper’s disturbing history

To better understand Ed Kemper’s Enneagram type, it’s useful to have a history of the actions that made him infamous. Feel free to skip this section if you’re already familiar with the story.

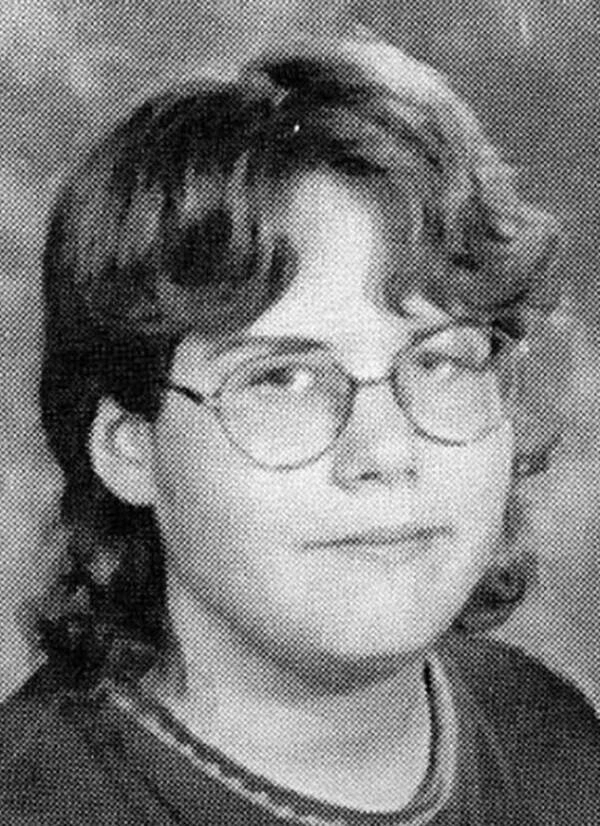

Kemper was born in California in 1948 to an overbearing mother and mostly absent father. His parents would complain bitterly to him about each other before they got divorced. His mother’s insults about his father in particular stuck in his mind, and he would grow up to experience many of the same negative views himself. Psychologists who look back on Kemper’s parents have suggested that his mother likely would have been diagnosed with Borderline Personality Disorder and alcoholism today. When his father moved out, Kemper blamed the dissolution on his mother and grew resentful.

Kemper moved to Montana with his mother, Clarnell, and his two sisters, one older and one younger. Clarnell began locking him in the home’s rat-infested basement every night without a bed or blankets. She cited concerns that Kemper would molest his sisters or her, which seemed to stem from his extreme height and weight rather than any actual instances of misbehavior.

He did exhibit other concerning behaviors, however: at ten years old, he killed the family’s cat by burying it alive, then dug it back up, decapitated it, and mounted its head on a spike. He did the same thing to a new cat his sister got several years later after he grew upset that it seemed to like her more than him. He dismembered it and stored its body parts in his closet as souvenirs.

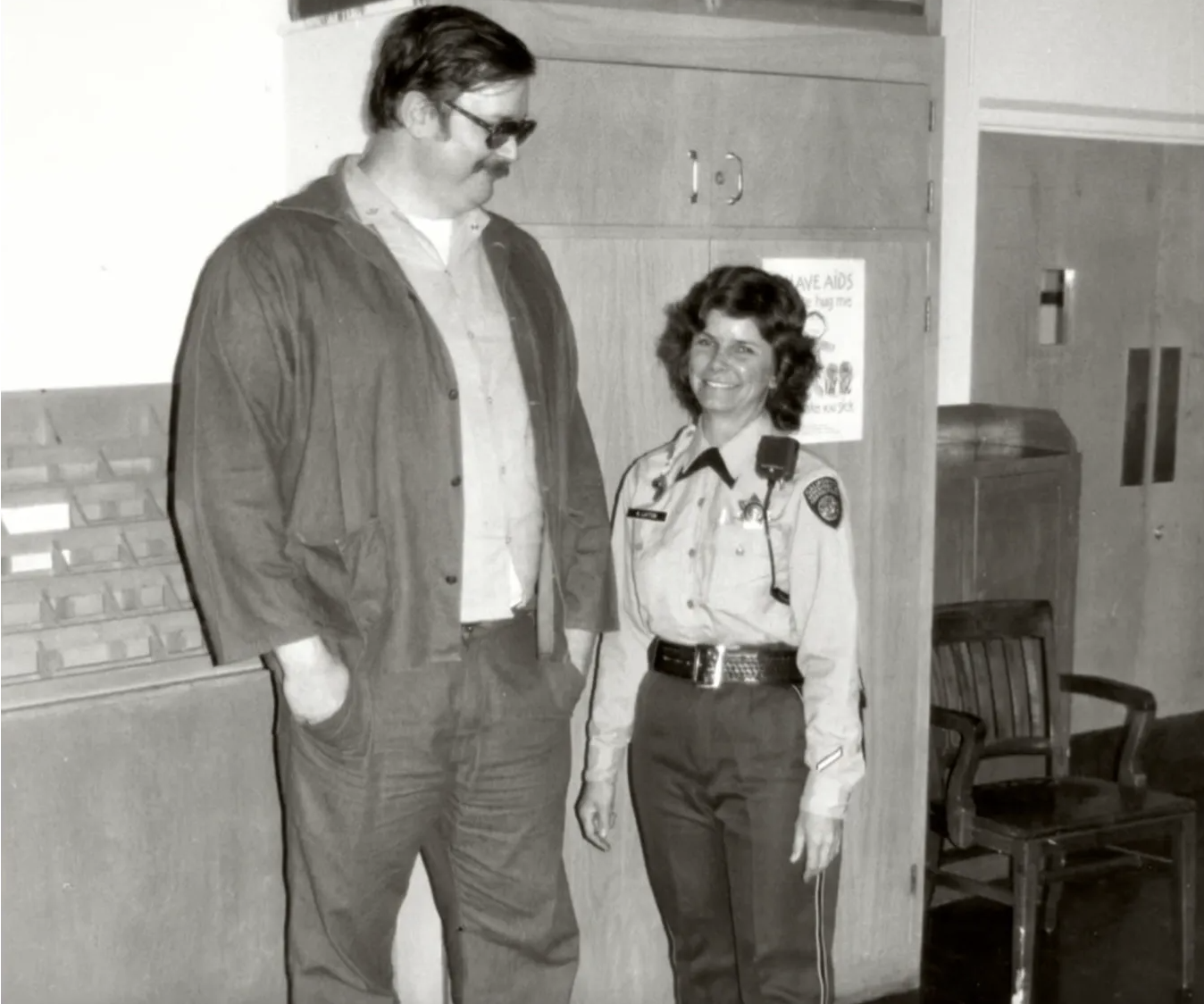

Isolated, cold, and frequently in the dark, Kemper’s loneliness and anger towards his mother festered. She withheld all forms of affection from him, saying that it was out of a fear that such “coddling” would “turn him gay.” It didn’t help their relationship that Kemper began to resemble his father as a teenager: he was 6’9,” over 250 pounds, with a big mustache. His mother viewed him as a constant, unwelcome reminder of her ex-husband and failed marriage, and she took out her contempt on her son.

At 14, Kemper couldn’t take the abuse anymore and ran away to find his father. His father, his girlfriend, and their stepson weren’t thrilled to be saddled with Kemper, so they sent him to stay with his grandparents (Kemper’s father’s parents). Kemper immediately disliked the dynamic he witnessed between his grandparents because it reminded him of his own parents: a large but mostly quiet man succumbing “to the whims of a bitter, haranguing woman.” He spent a lot of time taking his aggression out through hunting on his grandparents’ property. Soon, though, it wasn’t enough.

15-year-old Kemper’s anger at his grandmother boiled over after an argument on a summer day in 1964. He grabbed a hunting rifle and shot her in the back of the head, then twice in her back, while she sat typing at her typewriter. He then walked into the kitchen, took a carving knife, and stabbed her multiple times. This pattern of overkill on female victims—dealing far more damage than is necessary to inflict death—would become his signature. Kemper later told FBI agents when recounting this murder that he briefly considered sexually assaulting his grandmother’s corpse, but decided it was “too perverted” to act on. He then shot his grandfather in his car after he came back from grocery shopping.

Unsure of what to do after killing both of his grandparents, Kemper called the one person he hated most but knew would be available: his mother. He described what he’d done in a calm, measured voice. She told him to stay where he was and that she’d send the police. Kemper, always distrustful and detail-oriented, called them himself after hanging up with her just to make sure.

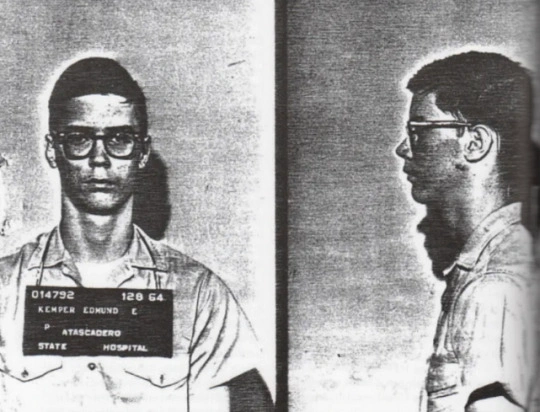

Kemper was arrested and tried as a juvenile for the murder of his grandparents. When asked why he’d killed them, he said he “just wanted to see what it felt like to kill Grandma” and then shot his grandpa so that he wouldn’t confront Kemper about it. He was diagnosed as a paranoid schizophrenic and sent to Atascadero, a California state hospital for mentally ill convicts.

Kemper lived in Atascadero from the ages of 15-21. He didn’t mind prison; his massive size discouraged anyone from messing with him, and he actually felt fairly secure because he had a consistent schedule, jobs to do (including administering psychiatric tests to other inmates), and plenty of time to read and collect knowledge from his fellow prisoners:

“He gravitated to a multitude of rapists and other sex offenders who gladly shared the details of their conquests, experiences, and techniques—most of which merged sexuality with dominance and violence—in self-glorifying detail [...] The teen not only studied what his new teachers had done, he paid particular attention to what they had done wrong.”

Kemper also loved the time he spent with psychiatrists and social workers. He appeared to cooperate with them, telling them what they wanted to hear so that he’d be classified as “normal” and released, while simultaneously compartmentalizing his morbid fantasies in his head. The complex psychological theories and tests that he heard about were fascinating to him: “Ed was sopping up the shrink-speak that explained his various disorders like a dry sponge.” It was around this time he learned that he had a genius-level IQ of 145, a fact that he took pride in.

When he was released on parole, Ed re-entered a world that had grown even more foreign to him. He was already socially awkward, even inept at times, and was painfully aware of his shortcomings. However, in juvenile detention he had developed formidable skill in manipulating the medical and judicial systems, and he used it to convince those in charge that he was rehabilitated. They expunged his records as a result, meaning that he re-entered the world after his stint in jail for murder with a clean slate. In a now ironic statement, his parole psychiatrists wrote about Kemper:

“If I were to see this patient without having any history available or getting any history from him, I would think that we're dealing with a very well adjusted young man who had initiative, intelligence and who was free of any psychiatric illnesses ... It is my opinion that he has made a very excellent response to the years of treatment and rehabilitation and I would see no psychiatric reason to consider him to be of any danger to himself or to any member of society.”

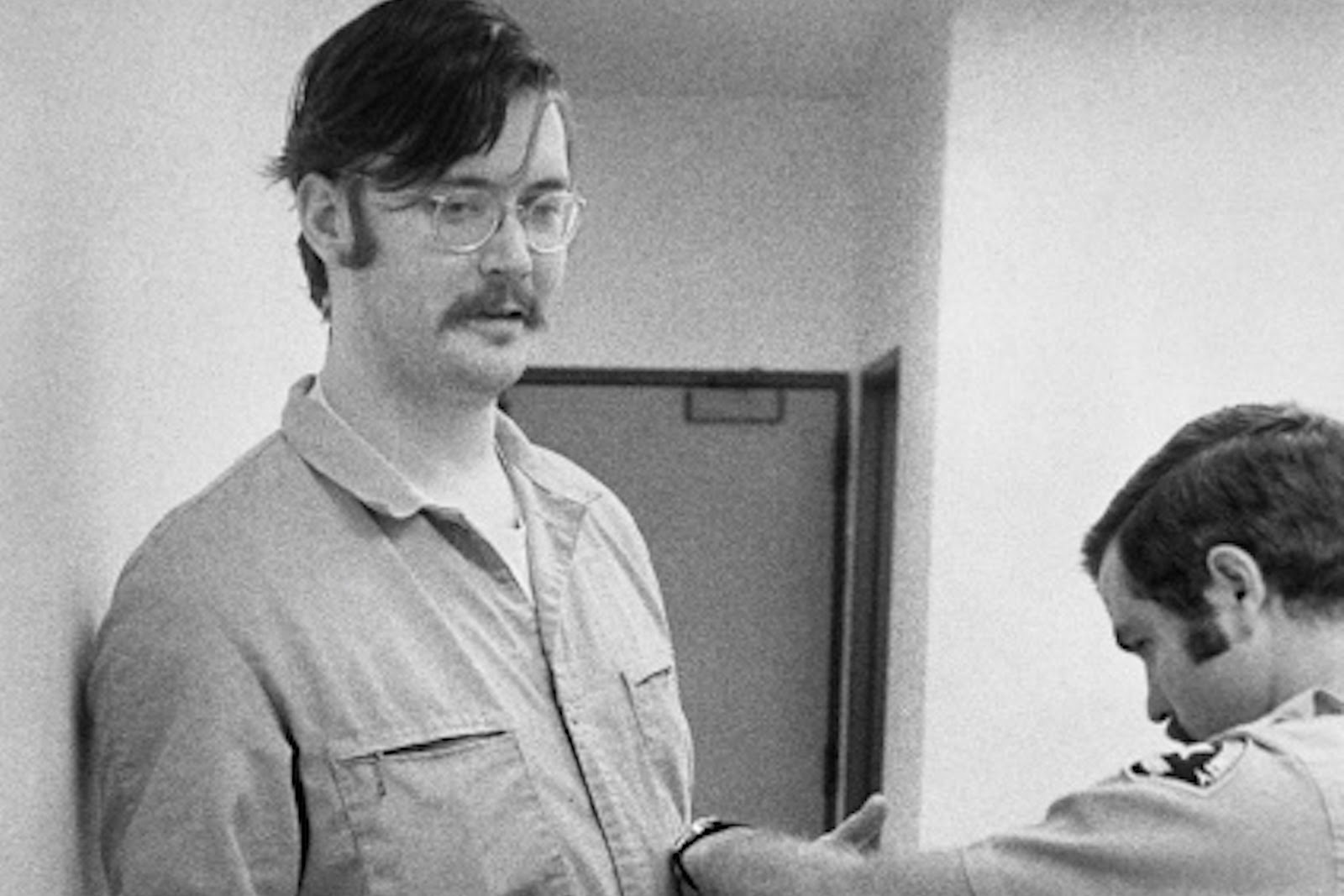

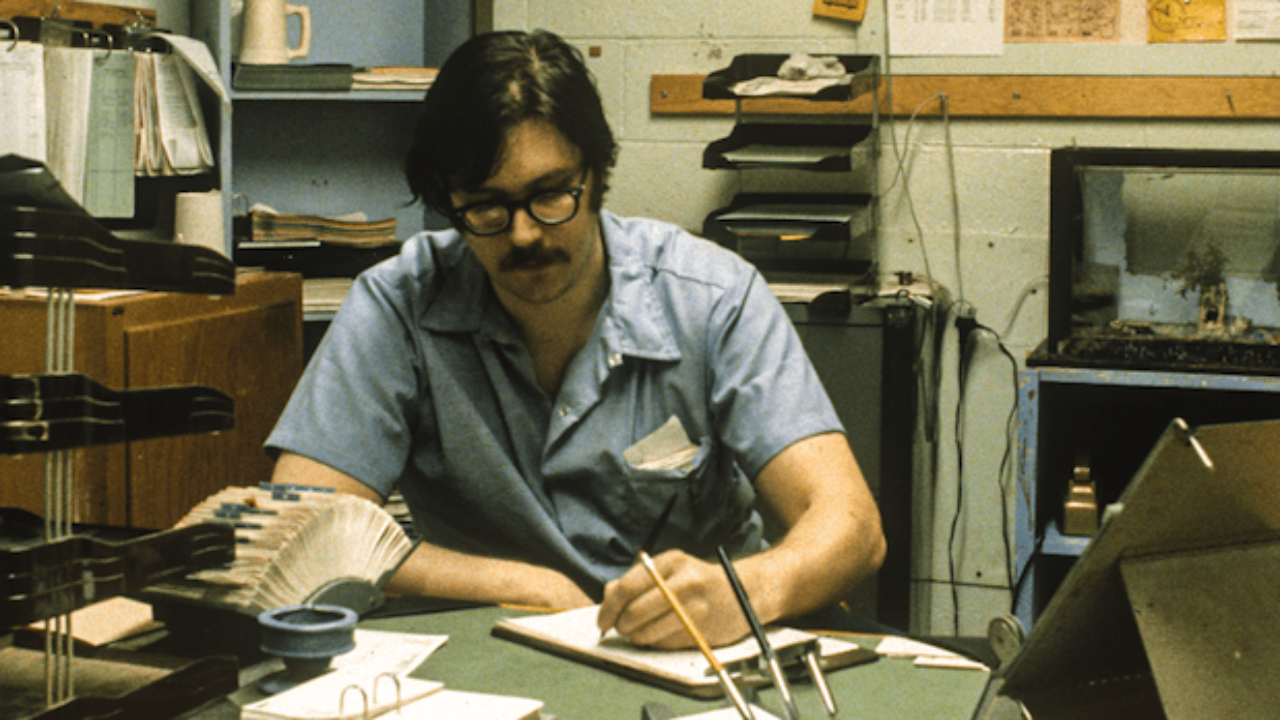

With nowhere else to go, Kemper moved back in with his mother. Their constant battles grew worse and wore on him. Yet he attended community college and pursued employment in several paths, including law enforcement (but was rejected for being above the height limit) and working with the State of California Department of Transportation. He got in the habit of hanging out with police officers at popular bars for law enforcement, where they gave him the nickname “Big Ed.” They saw him as a harmless guy who asked a lot of questions, but these relationships ended up being a great source of intel for him.

Kemper moved out of his mother’s house for a while and lived with a friend. He met his first and only girlfriend during this period, a high-schooler whom he got engaged to. He later told law enforcement officers that they never had sex, despite her wanting to: “She really wanted a physical relationship, kisses, flirting. It terrified me because I didn’t know how to react or control the emotions that germinated in me.” After introducing his fiancee to his mother went (predictably) badly, they broke up.

Both to get better at interacting with women and to entertain his dark fantasies, Kemper began to pick up female hitchhikers. He said, “At first, I picked up girls just to talk to them, just to try to get acquainted with people my own age and try to strike up a friendship.” But the more “he studied the girls closely to ascertain what they were about, what their interests were, and what worked and didn’t work while conversing with them,” the more he found the young women mystifying. One trick he learned was to look at his watch when girls were considering whether to get into his car: it was a subtle gesture that said “I don’t care whether you get in because I’m a busy person with things to do,” and it was the little push that many hitchhikers needed to accept a ride.

Kemper picked up over 150 young women in his 1969 Ford Galaxie, mostly from college campuses. He outfitted his car with “kill kits,” “various knives, swords, towels, blankets, garrotes, ropes, belts, handcuffs, and large plastic garbage bags were stashed in the massive trunk.” All the while, his murderous sexual urges roiled underneath his “harmless” facade. He knew he was going to act on them, but he felt that he needed an immense level of preparation before doing so: “Even though he was packed up and ready to go, Ed continued to research his pickups for over a year, giving up to what he estimated to be 150 free rides, studying and reliving each encounter, fantasizing about what he could have done.”

His first murders took place on May 7, 1972 and marked an 11-month spree. Kemper picked up two 18-year-old students who were hitchhiking from Fresno State University to Stanford University. He diverted off the correct path, pulled over, handcuffed one woman, and locked the other in the trunk. After he stabbed and strangled both of them, he had sex with their bodies. He put both bodies in the trunk of his car and drove back to his apartment. A police officer pulled him over for a broken tail light but didn’t notice anything else suspicious about Kemper.

Back at his apartment, Kemper took photos of the corpses and had sex with them multiple times before dismembering them and scattering the pieces on the side of various highways. He also had oral sex with the decapitated heads, a grotesque practice that would become another one of his signatures.

Kemper killed his third victim, a 15-year-old dance student, in a similar fashion: he picked her up, drove to a remote location, choked her, and began to rape her body. She regained consciousness during this act, though, which horrified Kemper. It would turn out to be the only time in his life when he had sex with a living person, and he did not like it. After he killed her, he drove to have drinks with his cop buddies and gloated at the fact that her body was right outside and they didn’t know. He treated her body the same way as his previous victims—almost as a hunting trophy—and scattered her remains once they were too decomposed to keep.

Kemper ended up moving back in with his mother soon after this third murder. Their arguments escalated:

“My mother and I started right in on horrendous battles, just horrible battles, violent and vicious. I've never been in such a vicious verbal battle with anyone. It would go to fists with a man but this was my mother and I couldn't stand the thought of my mother and I doing these things. She insisted on it and just over stupid things. I remember one roof-raiser was over whether I should have my teeth cleaned.”

Unable to contain his homicidal urges, and increasingly frustrated because of his dealings with his mother, Kemper went out for another victim. He found his fourth, an 18-year-old student who was hitchhiking. He repeated his pattern of behavior, killing, raping, and collecting his victim, but this time he took her body back to his mother’s house and hid it in a closet. He later described getting a thrill out of engaging in intercourse with the body all over his mother’s house and dismembering it in her bathtub. Finally he discarded her remains off the sides of roads, but he kept her head. He buried it in his mother’s backyard, facing up towards her bedroom. He later said that he did this because she “always wanted people to look up at her.

Kemper collected another two victims on February 5, 1973. By this time, news of missing students had spread in the area, and students had been advised to be careful when hitchhiking and only take rides from cars that had university stickers on them. Because Kemper’s mother worked at University of California Santa Cruz, he was able to get one of these stickers and continue to pick up unwitting victims. Two students got in his car on the UCSC campus; he later shot them, cut off their heads in his car, and brought them into his mother’s house to sexually assault their bodies.

His murder spree reached its conclusion a few months later on April 20, 1973. His mother came home late from a party and was sitting up in bed reading. Kemper came in, and she said to him condescendingly, “I suppose you're going to want to sit up all night and talk now." He said that he did not, left, waited for her to fall asleep, and returned with a claw hammer and a penknife. He beat her in the head with the hammer and slit her throat with the knife before decapitating her. “He then carried her head into the living room, put it on a shelf and screamed at it for an hour.’ His rage not yet satiated, he ‘threw darts at it’ before smashing in what remained of her face.”

Kemper continued his pattern of raping the severed heads and bodies of his victims, this time with his own mother. He described his actions as follows: “I came out of my mother. . . . I cut off her head. I humiliated her corpse. . . . Six young women dead, because of the way she raised her son. . . . And what’s her closing words? ‘I suppose you want to sit up all night and talk?’ I wish I had.”

When he was finished, he cut out her tongue and vocal cords (as they symbolized her insulting voice) and tried to chop them up in the sink’s disposal. Yet they got stuck and tripped up the grinder, shooting back out, which he viewed as symbolic. “That seemed appropriate, Kemper would explain “as much as she’d bitched and screamed and yelled at me over so many years.”

Kemper hid his mother’s body in the closet and got the idea of inviting his mother’s friend Sara Hallett, then killing her so he could make a cover story that his mother and Sara had left on vacation together and never come back. He called her over with the pretense of dinner and a movie. When she showed up, Kemper strangled her and hid her body in a closet.

Seemingly losing interest in the cover story he’d tried to manufacture, Kemper left a note for the police, loaded up on caffeine pills, and drove over 1,000 miles to Colorado. His paranoia grew along the way; he believed that police had engaged an active manhunt for him. But when he got to Colorado, he couldn’t find any news of the murders. Exhausted and paranoid, he started coming to terms with a realization that had been lurking beneath his consciousness: killing his mother was the act that brought all of his murders full-circle. His rage for her drove his homicidal urges, and now that he’d disposed of her, he was done.

When asked in a later interview why he turned himself in, Kemper said:

"The original purpose was gone ... It wasn't serving any physical or real or emotional purpose. It was just a pure waste of time ... Emotionally, I couldn't handle it much longer. Toward the end there, I started feeling the folly of the whole damn thing, and at the point of near exhaustion, near collapse, I just said to hell with it and called it all off."

Kemper called the police from a phone booth to turn himself in. The operators didn’t believe him and hung up. He called back several hours later, identifying himself as the “Big Ed” that the police knew, and giving details about the murders that only the killer could have known. Even then, they still thought he was joking. They picked him up and he began to ramble for hours with detailed confessions of all eight murders.

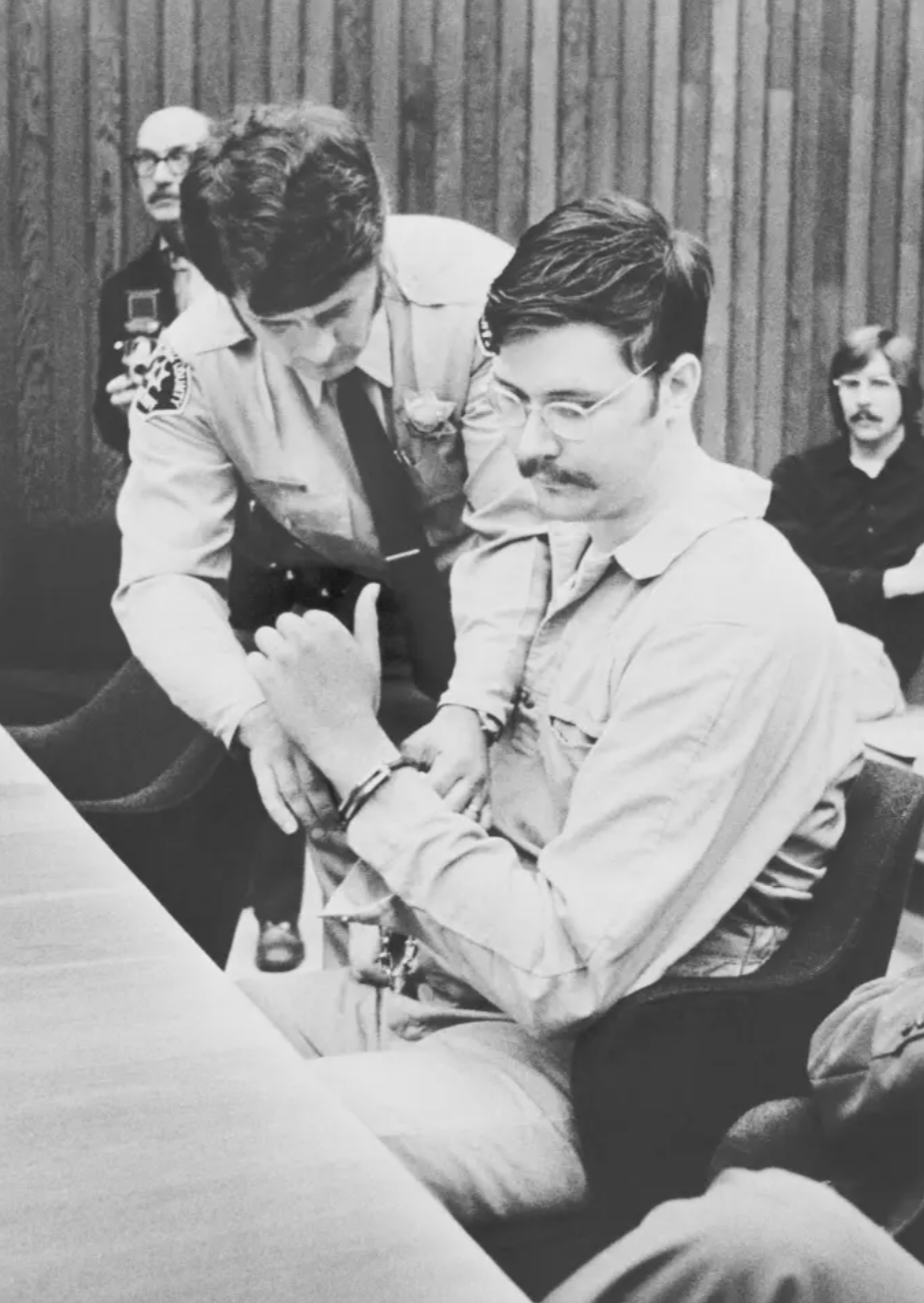

Kemper was convicted of eight counts of first degree murder on November 8, 1973. The only significant legal question during the trial was that of Kemper’s sanity, but the jury found him sane under the M’Naghten standard . He attempted suicide twice during the trial and requested the death penalty during sentencing (specifically asking for “death by torture”), which was denied due to the state of California’s moratorium on capital punishment.

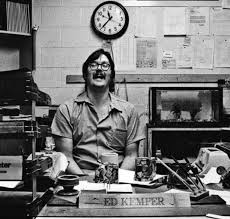

Unlike most other serial killers, Kemper’s “celebrity” stemmed almost as much from his time in prison as before it. He gained a reputation for being a model prisoner, taking pride in his work and seeking out volunteer opportunities. He was also one of the first killers willing to speak with the FBI’s new behavioral profiling unit (which served as the basis for the book and Netflix show “Mindhunter”), showing an unusual willingness to examine his brutal actions in a thoughtful, detached, and unemotional way. The FBI agents found themselves enjoying speaking with Kemper, despite knowing his violent history. Kemper is also one of the most prolific narrators of audiobooks for the blind with over 5,000 hours recorded.

Every time that Kemper has come up for parole, he’s either waived his right to appear or told the court that he belongs in prison and would be a danger to society: “Society is not ready in any shape or form for me. I can't fault them for that." He’s currently 73 years old and is next eligible for parole in 2024.

The profile of the low-health Five

According to the Enneagram, every person’s type stays the same across their lives. However, one may act out the best or worst versions of that type, depending on how much physical and emotional stress they’re under. Someone who’s under extreme stress is considered “low health” in the Enneagram. Although every type in high health is an exceptional person, every type in low health is the opposite, representing the worst potential of that type.

Low-health Fives are nihilistic and tend to isolate themselves from others as a form of self-protection. Their isolation reinforces their ruminations, which tend to take on an obsessive, negative quality, and they may spend all day and night stewing on their disturbing fantasies as Kemper describes: “I became interested with everything related to morbidity. I was fascinated by lots of things that revolved around death, destruction, and evil with a capital E.” Fives become overwhelmed by their intrusive thoughts and may be driven to act them out: “Nothing matters, so who cares what I do or who I hurt?” Help is the last thing on their minds because letting anyone observe their spiraling mental state might risk their primarily fear of being seen as incompetent..

Kemper describes living a dual life: he appeared normal and non-threatening on the outside, but his thoughts roiled with perversion and violence on the inside. He called this compartmentalized set of fantasies his “vicious world,” “an alternative reality he created inside his mind. There, he stored his dark thoughts and fantasies about death, sex, and violent acts against women.” He gave an example of the kind of thoughts he’d have regularly: “One side of me says, ‘Wow, what an attractive chick. I’d like to talk to her, date her.’ The other side of me says, ‘I wonder how her head would look on a stick?’”

Kemper likely spent most of his life in average to low levels of health, given his unstable and abusive family life. But he sank to new lows during his murder spree, especially in the few months before the end. He saw himself as physically and mentally superior to the cops he hung out with, and describes himself as getting increasingly paranoid and confident, a mix of states that don’t appear to go together but are often present in low-health Fives:

“As my crimes went on, I became more and more ill and I took fewer and fewer precautions, both in my approach, during and after, which seemed obvious to me given the growing amount of evidence that was discovered, in one form or another.”

Paranoia is another hallmark of low-health Fives. The more stressed they are, the more convinced they become that others are watching them or out to get them. Benign or random signs or symbols appear to low-health Fives as evidence that the universe is conspiring against them. Kemper fell into this trap as his kills piled up: “Ed was wildly overreacting to his paranoid fantasies of being captured. He was suffering from stress ulcers and starting to dive head-first off the deep end, mostly for no valid reason other than his increasing paranoia and horrific flashbacks.”

He became convinced that the police were onto him: “Kemper became more and more paranoid and had begun to lose his sense of rational thought. He began perceiving everything around him as a sign of his imminent capture.” Finally, Kemper’s rage reached its peak alongside his paranoia when he killed his mother, finally triggered by her insulting comment that night.

Healthy Fives tend to be detail-oriented, careful, and curious: they are aware of what they don’t know and don’t presume to have all the answers. Low-health Fives, however, may take on a black-and-white view of the world where they act like they know everything. Yet internally, they’re having immense trouble separating their dark fantasies from reality. Their bizarre perceptions may become all-consuming, pushing them to withdraw from the world entirely, make their fantasies a reality by acting on them, or a combination of both: “some suspected that Ed’s slaughters were so shocking to the human brain that they simply merged with his fantasies and nightmares to the point where he himself could no longer separate reality from fantasy.”

Even Ed himself had a sense that his fantasies were too strong:

“I knew long before I started killing that I would be killing, that it was going to end up like that. The fantasies were too strong. They were going on too long and were too elaborate.”

Collecting and avarice

Each of the nine Enneagram types is associated with a vice. The Five’s vice is avarice, but not in the traditional sense of greed or materialism. Rather, Fives want to consume as much information and knowledge as possible so that they feel competent to face whatever the world throws at them. Because Fives have a core fear of being incapable, they may hoard resources in order to feel prepared and to boost their sense of self. Despite many Fives living austere lifestyles and depending on as little as possible, they may invest lavishly on their hobbies. This apparent incongruity rises from the sense of meaning, purpose, and knowledge that many Fives get from their personal projects, which they deem worthwhile.

Kemper’s avarice reared its ugly head (pun intended) in his collecting of his victims and their body parts. He saw himself as a hunter and his victims as his trophies: “It [decapitations] was very exciting . . . there was actually a sexual thrill. . . . It was kind of an exalted triumphant type thing, like taking the head of a deer or an elk or something would be to a hunter. I was the hunter, and they were the victims.”

His fantasies all centered on him killing and triumphing over women (he wanted them dead, not alive). Possessing their bodies was the ultimate form of collection to him: “I imagine myself committing mass murders, where I gather a large number of pre-selected women in one place, killing them before passionately making love to them. Taking their life, possessing everything that belongs to them. All that would be mine. Absolutely everything.”

Because bodies couldn’t last indefinitely due to decomposition, Kemper hoarded other souvenirs. He took Polaroid photos of his trysts with the decapitated bodies and “kept the coeds’ personal items in his room for weeks afterward, studying their family photos, makeup, hairpins, hairbands, and everything else young women carry in their pocketbooks.” The way that he scattered the victims’ dismembered body parts in bags was designed to fit his mental map of the locations, so that he could visit them repeatedly to relive the experience and “keep their spirits close.” He found it hardest to part with the skulls, even burying one in his mother’s backyard.

Stealing his victims’ lives, bodies, and personal property were not enough for Kemper. The nature of avarice is always needing to have more. “He had hoped the photographs he had taken (and cherished) of the carnage would be enough to satisfy him and calm the savage beast—possibly forever—but was dismayed to learn that their potency had a psychological shelf-life of ‘two weeks.’” Years later in prison, he would tell interviewers that his pull to collect and possess women was simply too strong to avoid: trying to ignore his fantasies had been futile, and he always would have acted on them. This realization was also why he never pushed for his release from incarceration.

Incompetence with women

It appears fairly straightforward (and he has supported this hypothesis himself) that Kemper targeted women as a way to take out his frustrations in failing to interact successfully with them. He said, “I was scared to death of failing in male-female relationships.” He could befriend men, but “he was, and would forever be, admittedly inept at basic interaction” with the opposite sex: “Kemper was afraid of women. He felt awkward and irritated around them although he craved companionship. The more awkward he got around women, the more he began to resent them […] Reclusive, often sullen, and socially inept in the outside world, Ed once again began to struggle mentally and socially.”

Fives crave competence and avoid looking foolish or dependent. Thus anything or anyone who continually reminds them of their incompetence can become a focus of their dislike (or even hatred, in low health). For Kemper, women were that symbol of failure. He said, “I always felt intimidated by women. I always felt overpowered by them as a kid. . . . I was doing great sociality on the job base, making friends locally. Having buddies and stuff. Have a pizza and a beer and stuff. No problem. I got friends for that. But making women friends was real tough.”

Determined to improve his poor socialization skills with women, Kemper set his sights on researching and practicing with hitchhikers. He gave rides to over 150 women in a single year to try out different tactics, lines, and topics of conversation: “At first, I picked up girls just to talk to them, just to try to get acquainted with people my own age and try to strike up a friendship.” He kept trying and kept failing. Part of his failure stemmed from his standards for beauty, which he admitted were much higher than were reasonable.

He realized somewhere in the midst of this experiment that he stood no chance with the types of women that he was attracted to (mostly attractive and socially adept college students), at least not while they were alive: “his year of male-female courting-interaction research, combined with the subsequent chat-up failures, had convinced Ed that he was a vulture, not a hawk. He wanted nothing to do with live victims.” A living victim could insult Kemper, fight back, and remind him of his inadequacies. But a dead one couldn’t do anything but submit.

If Kemper is indeed a Five, his inadequacies with women provide a fitting reason for his violent behavior because they strike at the core of his fears. Kemper punished the type of women who he felt rejected him. They also shared a connection with his mother: “I was involved in killing coeds because my mother was associated with college work, college coeds, women. . . . My mother was a sick, angry, hungry and very sad woman. I hated her.”

Psychiatrists who have profiled Kemper further describe his inferiority complex, linking it to his sexual performance: “Kemper was driven by manic sex urges but saddled with a crippling sense of inferiority. He had a small penis, which on him looked minuscule, and was quite inept as a lover…Other accounts reported that Ed tried, but couldn’t finish, with a live woman—contrasted with how fast he said he could release with a dead one; twenty seconds or less!”

Ironically, Kemper’s incompetence with women translated (morbidly) into a competence that he became famous for: deviant murder. He built an expertise around killing, becoming a sought-after interview subject while he was in prison. “Kemper enjoyed the attention; it gave him confidence in other areas of his life. It was the first time he perceived himself as successful at something, and people were recognizing his success for the first time.” And likely because he feels competent in prison (and incompetent outside it), he has never argued for his release.

“When he met with the parole board assigned to him, he told them that he did not feel ready to be released. He is happy to go about his life in prison and doesn’t trust himself in the outside world. It’s a place he doesn’t understand, and he doesn’t think he ever will.”

Withdrawn, avoidant, and “invisible”

Fives tend to be withdrawn in social situations, preferring to observe. They are thinking types who spend a lot of time in their heads. Gaining an understanding of what a given context calls for before they interact is important to them, as they don’t want to be caught off guard. Most Fives tend to be introverted and can make themselves disappear in groups until they’re ready to contribute. Fives will often describe that they feel a certain safety in blending into the crowd, where they can see others but not be seen themselves.

Kemper appears to have the Five’s desire and ability to go unseen: “Despite his ominous size and appearance, he emerged from Atascadero like a ghost—unknown and unnoticed by anyone.” He said of his notoriety that “I absolutely do not want to be the center of this attention, I want to blend into the crowd.” In some of his fantasies, he wanted to be left utterly alone to avoid having to deal with another person ever again: “Ed began to wish, and actually pray, not only that his abusive mother and sisters would die, but that everybody else in the world would be erased as well, leaving him to exist in peace.”

Kemper was also strangely avoidant and non-confrontational during his murders, as if he wanted to be invisible while committing them. He shot both his grandparents in the backs of their heads so he wouldn’t be confronted by their shocked faces. He tried to kill his hitchhiker victims quickly and with them facing away from him, and was disturbed and shaken when things did not go according to plan.

He described being mortified when he accidentally brushed a living victim’s breast, and mumbled an apology before killing her. And when another victim that he thought he’d strangled to death woke up while he was raping her, he was so unsettled that he couldn’t continue performing sexually. “This avoidance was perplexing for a boy—and then the man he would become—who craved killing and got off on experiencing the death of animals and people up close and so very personal. And yet it would be part of Ed’s cowardly MO from that point on, even during the shocking post-mortem rapes he’d commit later.”

Ed once said about his own “invisibility:”

“The one thing that amazes me about society is that you can do damn near anything . . . and nobody is going to say anything or notice. . . . I started flaunting that invisibility . . . severing the human head, two of them at night, in front of my mother’s residence.”

Things, not people

Fives are cerebral people who tend to love talking about concepts, not people. For example, it’s likely that a Five will prefer having an in-depth conversation about a project they’re working on or a philosophical theory they’ve been studying, rather than unpacking the “who/what/why” behind which friend is dating which person. If they do take an interest in people, it’s in a detached, analytical way and typically in service of building a robust mental model of how people work.

Taken to an extreme degree with a low-health Five like Kemper, this “things, not people” tendency shows itself in his interest in his victims’ bodies, not their personalities: “Ed Kemper in particular craved the dead bodies of his victims more than he got off on taking their lives.” Interacting with inanimate objects gave Kemper freedom to act without being observed, restricted, or judged. Kemper said, “If I killed them, you know, they couldn’t reject me as a man. It was more or less making a doll out of a human being . . . and carrying out my fantasies with a doll, a living human doll.”

Interacting with an object, not a person allowed him to experiment as much as he wanted without rejection: “I just wanted the exaltation over the party. In other words, winning over death. They were dead and I was alive. That was the victory in my case […] I can do anything I’m curious about. Do anything I only dreamed about doing, and nobody can do anything about it. Power is a big part of it. But extreme sexual pathology is another.”

Stripping the life from his victims’ bodies left Kemper with objects that he felt comfortable with. While a living, breathing woman could always emasculate him with her actions or words (as he felt that his mother did), an object could not. Yet Kemper still sometimes read a certain willfulness into the body parts, as if they were trying to make him feel incompetent even in death: for example, viewing the disposal’s failure to eviscerate his mother’s vocal cords as a final act of her resistance.

Unemotional and logical

Fives gravitate towards reason, logic, and objectivity to make sense of their world and their role within it. They experience emotions, but they tend to minimize them in order to function. Fives spend a lot of mental energy constructing models of how things work, and then tweaking those models as they get new information. They can have a lag between experiencing life in the moment and processing the sensations and emotions associated with it after a delay. As a result, Fives may appear somewhat “robotic” and unemotional in their exteriors, despite having a rich inner world of feelings. He was full of conflict, torment, and intense feelings, everything from rageful outbursts that led to him murdering his own family, to turning himself in out of remorse, requesting that he be tortured and lobotomized.

Kemper’s life followed the pattern of withdrawn states punctuated by intense and brief periods of rage. He snapped and killed his grandparents, then calmly explained his actions on the phone to his mother. “The 15-year-old never denied his actions or fought with the authorities; he was always obedient, honest, and cooperative.” He killed his mother and her friend, then turned himself into the police and confessed to all the details. Experts said of Kemper that “He has a sociopathy or a psychopathy. He can be completely dispassionate while he is killing another person.”

Kemper comes off as composed and unemotional in interviews . Even when the topics he discusses are highly emotional and irrational, he still discusses them in a straightforward manner. For example, when interviewers asked him why he raped his mother’s dead body, he said, “‘I came out of my mother’s vagina and in a rage I went back in,’ he explained, ever professing a logical basis for his perversions.” The candidness he showed in talking about his own heinous actions and psychopathy made him a valuable interview subject for law enforcement. Contrast Kemper with a killer like Ted Bundy , who hid the full depravity of his actions and attempted to manipulate interviewers for his benefit.

Kemper even took a “logical” approach to his own treatment. He asked the court to put him to death via torture, as he felt that would be a fair response to the pain he caused others. When that request failed, “He asked for a partial lobotomy explaining if they could take out the part of the brain that controls violence, perhaps he had a chance for parole.” He comes across as a person who is tortured by his disordered mind, yet knows it’s maladaptive and is willing to remove himself from the general population because he will always pose a threat.

Sponge for knowledge and research

Fives want to be capable, so they preserve their mental clarity by accumulating knowledge and observations. Knowledge is protection and power to them. There is always something to be learned or some insight to be gleaned from a person or situation.

Kemper studied the world like a textbook. He even framed some of his worst actions as quests for knowledge: for example, famously stating that he just wanted to see what it felt like to kill someone after murdering both of his grandparents. When asked why he committed all his crimes many years later, he gave a similar answer: “he had always wanted to know what it felt like to take a life. Now, he finally knew.”

In prison, he glommed onto the psychiatrists treating him and the criminals surrounding him, extracting as much information from both as he could. “With his intelligent brain, Kemper was good at reading between the lines of the disturbed individuals. He would listen to their accounts of their crimes and turn the information into a how-to guide of sorts, all while convincing doctors he was overcoming his dark urges and desires.” He learned how to hide his urges, not fix them. He took in his doctors’ words, not to take their advice, but to adapt to what he needed to say and do to be seen as “normal,” including memorizing 28 “correct” answers to psychological assessments in order to be released into society.

Discovering that he had a genius-level IQ pleased Kemper immensely. He had always known he had an active mind that hungered for knowledge, but now he knew that he was “superior” in his intelligence. Confidence was lacking in most other areas in his life, but he knew he was smart, and that sometimes led him to think of himself in grandiose ways: “Ed forever fancied himself a shrink—a ‘sociologist,’ actually, he once said—figuring that his years of interactions with doctors of the mind were similar to years of formal study for a degree.”

Desire to educate

Because Fives tend to be driven to acquire knowledge and understand concepts deeply, they often have a related interest in educating others. Retreating into their research materials and their minds to hone their theories is rewarding, but sharing what they’ve learned with others can be especially meaningful. Fives often fit the archetype of the pioneering inventor who returns from their studies to enlighten others with their discoveries.

Kemper’s behavior fits with the Five’s desire to educate, albeit in twisted ways. He came to view his crimes as “educational” in the sense that he “taught women not to hitchhike.” “Ed believed the young girls he picked up were ‘stupid’ to be taking such a risk, and felt it was justified if anything bad happened to them.” Despite this being a deluded and callous take, it’s true that the wave of murders he caused in the early 1970s changed the public’s view of hitchhiking forever (alongside a few other killers acting at the same time).

Kemper’s willingness to talk in depth about his crimes and state of mind for the sake of better understanding and predicting serial murderer behavior was unprecedented: “He freely offered himself up as a willing case study for doctors, law enforcement, FBI profilers, and every level of media.” When asked why he opened up, he said, “Maybe they can study me and find out what makes people like me do the things they do.” Kemper believed that his words could reach someone wired similarly to him who was struggling with his own dark fantasies, and potentially refrain from acting on them:

“They need to talk to somebody about it. Trust somebody enough to sit down and talk about something that isn’t a crime. Thinking that way isn’t a crime. Doing it isn’t just a crime, it’s a horrible thing. It doesn’t know when to quit and it can’t be stopped easily once it starts.”

Although Kemper’s openness was a valuable resource, he tended to get into too much unnecessary detail. This style of sharing excessive data is something that Fives tend to do regularly. Because they want to know all the facts, they assume that others do, too. When applied to the grotesqueness of his crimes, Kemper’s desire to educate others down to the last detail became too much for many listeners to bear. During the drive back to the police station after his final murder, Kemper started confessing to all of his crimes in such gory detail that the officers asked him to stop. “I hate to get into such detail on that [his slaughters and mutilations], but my memory tends to be rather meticulous,” he said.

Preparation

Fives accumulate knowledge and experience so that they can feel prepared to perform when needed. In Kemper’s case, his preparation centered on gaining the skills to acquire desirable female targets, kill them with as little confrontation as possible, act out his fantasies, and escape detection. He “viewed his kills as a game in which he was learning the best way to play.”

The detail-orientation of Fives combined with their ability to reach obsessive levels of depth in research can amount to excessive levels of preparation. Where another personality type might think “I’ve done enough,” a Five may do another hundred practice runs. Almost no amount of preparation feels sufficient. This tendency leads Fives to be masters of their domains, yet paradoxically fail to think of themselves as experts.

Kemper’s preparation started with his free rides to female hitchhikers, “giving up to what he estimated to be 150 free rides, studying and reliving each encounter, fantasizing about what he could have done.” He stashed “kill kits” in his car, swapping out and adding items that he felt he needed based on his interactions with the women. One addition he made was that “he rigged his passenger door so that it couldn’t be opened from the inside anymore. Once inside, passengers had no way out unless Kemper allowed them to exit the vehicle.” The details of small talk—what worked and what didn’t to put the women at ease—occupied his mind.

On May 7, 1972, Kemper felt prepared enough to put his planning into place with his first victim. He would later describe his preparation in a 1984 interview : “It was something that had been thought out in fantasy, acted out, felt out, hundreds of times before it ever happened.” Even then, things didn’t go according to plan: he had far more interaction with his living victim than he wanted, and she was harder to kill than he anticipated. He replayed the encounter in his head, fantasizing about it but also learning from the experience.

Subtypes and wings: why is Kemper a 5w4 and not a 5w6?

Here are both Five subtypes for comparison:

5w4

The Iconoclast is inventive, cerebral, intellectually-intuitive, unassuming, abstract, eccentric, disconnected, subversive, and reclusive. They are contemplative and astute explorers, but can be antagonistic and nihilistic.

5w6

The Problem-Solver is investigative, knowledgeable, meticulous, logical, skeptical, collecting, socially awkward, argumentative, and paranoid. They are multi-skilled practical thinkers, but can be rejecting and belligerent.

While both Five subtypes share the basics—a desire for competence, a fear of lacking resources, etc.—they differ in a few key areas. Problem-Solvers tend to focus on attaining skills and knowledge in better-known fields, whereas Iconoclasts are more likely to pave the way in truly unique, “never been done before” areas. Because of their Six wing, Problem-Solvers also tend to have a more palpable level of anxiety, whereas an Iconoclast’s anxiety is far less present or palpable. And because of their Four wing, they are usually much more interested in deep introspection than Problem-Solvers are.

Kemper is certainly iconoclastic. It’s hard to say that he isn’t unique in how he chose to commit his murders and his willingness to talk about them later. Part of his endurance in the public eye is because there’s no killer quite like him.

Iconoclasts, especially those with a strong Four wing, harbor a feeling that they never fit in anywhere and that no one fully understands them as Kemper reveals, “I always felt like a social outcast. I never managed to find my place.” This psychological evaluation of Kemper hits on each of these Four traits:

He “passively resists fulfillment of routine social and occupational tasks; complains of being misunderstood and unappreciated by others; sullen and argumentative; expresses envy and resentment toward those apparently more fortunate; voices exaggerated and persistent complaints of personal misfortune; alternates between hostile defiance and contrition.”

The Four wing lends itself to thorough self-examination, making many Iconoclasts explorers of both outer and inner space. Kemper’s readiness to talk through the details of his life and actions exemplify this. One of his doctors commented that “Kemper’s extremely high intellect, combined with his willingness to painstakingly describe his kills, his damaged upbringing, and his motivations in extraordinary detail, make him a valuable case study.”

Iconoclasts are generally moodier and more in touch with the changing energy of psychological states than Problem-Solvers are. They often manage to keep an unassuming and disconnected presentation, even if their internal state is turbulent. Kemper describes this tension in an interview:

“I was raging inside, there was just… incredible energies… positive and negative. Uh… depending on a mood, that would trigger one or the other. And outside, I looked troubled at times, other times, I looked moody. Uh, other times, perfectly serene. Not very sane. But again… people weren’t even aware of what was happening.”

Their Four wing pulls Iconoclasts more towards surfacing the significance of events. Whereas Problem-Solvers tend to focus on how things work, Iconoclasts tend to go deeper into the “why” behind them. They often ascribe enhanced meaning to their behaviors to tell a cohesive story as Kemper does when he looks back at his actions and describes them through a lens of symbolic and personal meaning:

“My little social statement was I was trying to hurt society where it hurt the worst and that was by taking its valuable members, or future members of the working society that was the upper class or upper middle class. . . . I was striking out at what was hurting me the worst, which was the area, I guess deep down, I wanted to fit into the most and I had never fit into, and that was the group, the in-group.”

He also describes killing his mother as the crescendo of his “work,” given its psychological importance, and frames all his kills as motivated by his hatred of his mother:

“After several days of running, Kemper gave up. He decided that he didn’t want to be on the run anymore. Psychologically, he felt like he had completed his life’s mission, and he had started to become annoyed that he hadn’t been given any recognition yet. As well, he knew he had no means of survival without his mother.”

“[My victims] represented not what my mother was, but what she liked, what she coveted, what was important to her, and I was destroying it.”

Lastly, Iconoclasts in low health can be the most nihilistic of all the types. Kemper turning himself in once he felt his mission of getting revenge on his mother was fulfilled, his complete and detailed confessions, his suicide attempts in prison, his request for the death penalty, and his lack of desire to ever leave prison all suggest a person who has given up on much of the premise of a normal life.